Last week, the U.S. Surgeon General issued an advisory entitled “Alcohol and Cancer Risk 2025” which garnered a significant amount of media attention since it concludes that the consumption of alcohol is so risky that all alcohol sold in the U.S. should contain warning labels to alert consumers about the cancer risks caused by alcohol consumption. It includes some worrying statements such as that the risks of alcohol related cancer “may start to increase around one or fewer drinks per day”.

In many places, it emphasizes the risks related to low levels of consumption including by stating that “17% of the estimated 20,000 U.S. alcohol-related cancer deaths per year occur at [consumption] levels” within the U.S. recommended drinking guidelines of 2 drinks per day for men and 1 drink per day for women. It also asserts that the majority of the public is uninformed about the extent of such risks.

The end of the advisory concludes with a call to action for “reducing alcohol-related cancers in the U.S.” that includes a reassessment of recommended consumption levels as well as advocating for the inclusion of warning labels “about the risk of cancer associated with alcohol consumption”. Here is an excerpt:

I am not convinced that this advisory is correct or that it even provides useful information for the general public. Here’s why I think that.

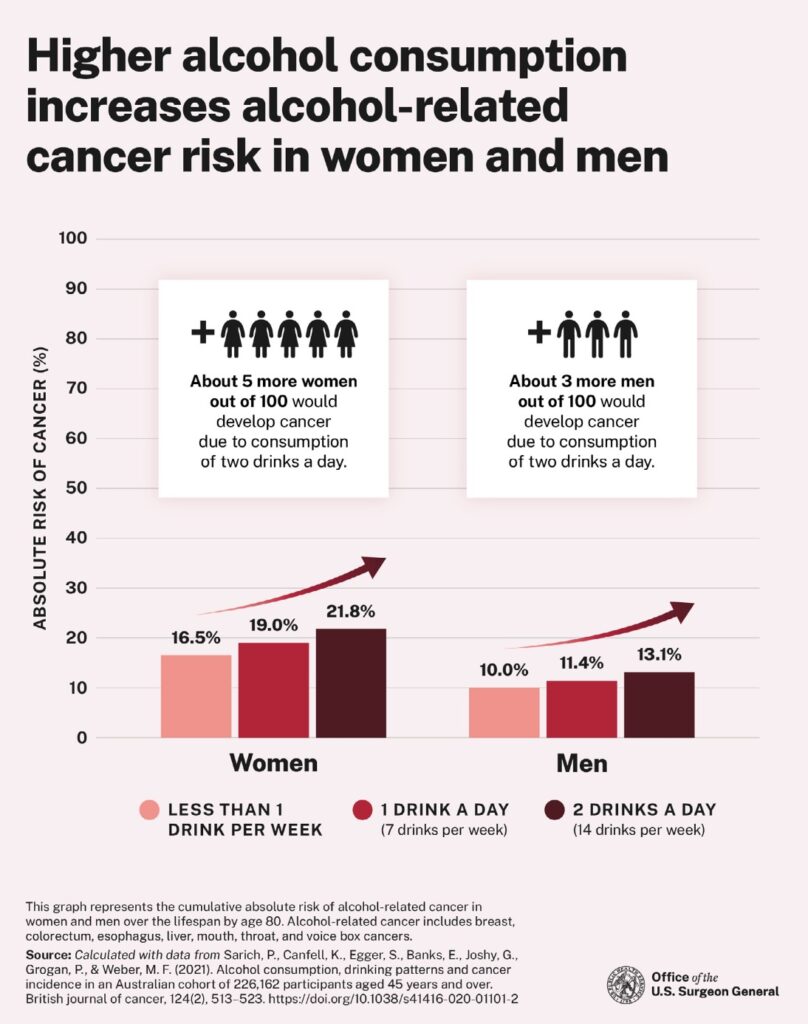

A major part of the advisory, and one that is of interest to the public, is an explanation of the risks related to alcohol consumption … and specifically how those translate into the likelihood of poor health. While there is some reference in the advisory’s discussion to other sources, the most “hard-hitting” part of it (and the easiest to understand) is an infographic (shown below, from p.13 of the advisory) which concludes that more alcohol consumption (even at relatively low levels) increases the risk of cancer in both men and women.

It states that the lifetime risk (up to age 80) of being diagnosed with an alcohol-related cancer is 16.5% for women and 10% for men if they drink less than 1 drink per week (i.e. this is the chance of getting one of these types of cancer even if you drink basically nothing). It then asserts that these risks increase to 19% for women and 11.4% for men at a consumption level of 7 drinks per week (the current U.S. recommended level for women). The risk further increases to 21.8% for women and 13.1% for men at a consumption level of 14 drinks per week (the current U.S. recommended level for men).

The infographic further explains that these increases in risk would translate to “about 5 more women out of 100” and “about 3 more men out of 100” developing alcohol related cancer (up to age 80) if they consumed two drinks per day (i.e. about a 5% increase for women and 3% increase for men in absolute risk).

All of these infographic explanations of risk are based on a single study from Australia that was published in 2021. Here is the link to the study if you are interested. After reading through the study, I am having considerable difficulty in understanding both how the Surgeon General came to the conclusions that he did … and how the conclusions regarding risk were generated.

The authors of the study generated conclusions of risk related to alcohol consumption that are similar to the ones contained in the advisory. These are tabulated by age and gender and by alcohol consumption groups (see excerpt from table below which highlights the important parts, the complete Table 3 can be reviewed as part of the supplementary material to the study which can be found at the link above.

If one reviews the actual assessments of risk calculated in the study up to age 80 (table 3 above – in red), one can see that the study determined the following:

- The lifetime risk for alcohol related cancer for those in the group who drink less than 1 drink per week (i.e. almost nothing) is 9.96% for men and 16.53% for women. These numbers are the same as those in the advisory infographic (above) and indicate the chance of being diagnosed with an alcohol related cancer even if you drink next to nothing.

- The lifetime risk for alcohol related cancer for those in the group who drink amounts between 1 and 14 drinks per week (median/average of 6 drinks for men and 5 for women) is 10.86% for men and 17.6% for women. This is an increase of about 1% in the absolute risk to the first set of numbers (i.e. little difference in risk to drinking almost nothing). The advisory infographic provides a different set of higher risk numbers (11.4% and 19%) for consumption at 7 drinks per week which it is claimed is based on the same data.

- The real problem lies in the final set of numbers. Here the lifetime risk for alcohol related cancer for those in the group who drink more than 14 drinks per week is calculated for everyone in that group who declared above this consumption level and for all greater consumption amounts (some of whom would be heavy drinkers … the median/average consumption in this group was 21 drinks per week for men and 20 drinks per week for women – see red text above). The lifetime risk to age 80 for this group is stated as 13.46% for men and 21.17% for women. These risk percentages are almost the same as those quoted in the advisory infographic (13.1% and 21.8%) for a consumption level of 14 drinks per week. This makes no sense. How can the analysis from the actual study indicate a risk level for a group with a median consumption of 20-21 drinks per week that is quoted by the advisory as being essentially the same as one for 14 drinks per week. One set of numbers appears to be incorrect … and that is more likely to be those in the advisory infographic.

This is potentially serious because the infographic is claiming a particular level of increased risk at 14 drinks per week (which are the current U.S. drinking guidelines for men) which does not appear to be justified by the study upon which it relies. According to the study, that same level of increased risk is not reached until (on average) men drink 50% more than the guidelines and women drink 185% more than the guidelines.

As such, I question the propriety of the conclusions in the advisory. In addition, and since the advisory relies so much on the Australian study, it is worth noting the following:

- The study group consisted of individuals over 45 years of age. Persons living in rural and remote areas were over-represented in the group. These factors raise questions related to the transferability of the conclusions to other demographic groups in other places such as the U.S. The authors note that the study’s conclusions regarding risk are higher than other studies, particularly a British one.

- Vital information related to lifestyle and alcohol consumption was obtained from the group by self-reporting via postal questionnaires. This raises questions about the accuracy of the data including the likelihood of under-reporting of alcohol consumption.

- The authors of the study note that 2.8% of cancer cases in Australia are attributed to alcohol consumption. Conversely, this means that 97.2% of cases are NOT attributable to alcohol.

- The authors note many limitations of the study including the possibility of under-reporting of consumption by participants and an inability to fully track consumption patterns or alcohol types.

In summary, I have the following questions about this advisory that raise issues about its utility:

- Why is the Surgeon General using a single Australian study to provide risk justifications for alcohol policy interventions at the federal level for all of the United States? This particular study may not be applicable to the U.S. and/or could later be proved to be inaccurate.

- Policy decisions that are based on science should have broad scientific support. In contrast, the recent National Academies Review of Evidence on Alcohol and Health came to dramatically different (basically opposite) conclusions regarding moderate consumption and appears to be broader based.

- Why is the Surgeon General’s advisory using risk calculations that do not seem to be supported by the actual data in the study that it is relying upon?

- Why is the Surgeon General’s advisory narrowly focused on the health risks related to alcohol and cancer, particularly when the vast majority of cancer cases (97% according to the Australian study) are not attributable to alcohol consumption? Should the Surgeon General more properly be taking a broader look at alcohol and health … as the National Academies Review did?

- Why would relatively small increases in risk justify a conclusion that alcohol “causes” cancer (a more accurate statement might be that “alcohol can contribute to the development of cancer” at specified consumption levels)? Why would this lead to calls to reassess the existing drinking guidelines? And why would this lead to advocacy for warning labels that could be very misleading in respect of the actual risks involved?

Note: my discussions of risk above refer to absolute risk which is the primary discussion in both the advisory and the study … and, in my view, the most transparent way to discuss risks relating to health. I do not refer to relative risk (i.e. the % difference between two levels of absolute risk) because I think that is often misleading, particularly in situations where the absolute risk is small.